The 80/20 principle/rule has recently caught my eye in a couple of places – some have liked it and some have not. I like it, and I thought I’d briefly explain why.

How Did the 80/20 Mindset Regarding Weight Management Originate?

Eating according to the 80/20 principle means that 80% of eating should be healthy and high-quality, and 20% of the food can be of lower quality, allowing for flavor and flexibility in eating all kinds of food. This can refer to the overall quality of eating over a period of time or how often the smarter choice should be made.

And from this, various practical applications can be drawn:

“not every piece of bread needs to be whole grain as long as the majority is”

“you don’t need to worry about moderate alcohol consumption at a friend’s cottage trip as long as moderation is under control in everyday life”

“something less sensible can fit into every day if the majority is still healthy”

“good eating doesn’t have to succeed every single day as long as you eat well most of the time”

Many Have Influenced the 80/20 Mindset

A quick Google search also finds numerous hits for the principle. I have even heard some say that I am the creator of this principle. Yes and no. It is true that around the turn of the millennium, it occurred to me that this would be a good ratio to describe what good eating is like – as it was a suitable ratio, and it’s not about 100% healthy choices, as there are other names for that. If not quite orthorexia, then at least tragicomic seriousness.

I actively spread the 80/20 rule, and in Finland, it has caught the eye of some. However… it wasn’t long after “inventing” the principle when I saw the same principle in an Australian researcher’s presentation – and it has since consistently appeared here and there around the world.

The principle has indeed been invented by many! Perhaps there is something appealing about that ratio, as in the world of economics, the same ratio is known as the

Health Promotion Supports Weight Management

In my mind, the 80/20 mindset began to take shape when, at my first workplace, the UKK Institute, the health benefits of exercise were communicated (rightly so) in such a way that the health benefits obtained from exercise are greatest when there is very little exercise, but for someone already exercising quite a lot, further increasing exercise does not bring many benefits and gradually even increases risks.

A similar message was not very visible in eating, but it was quite logical for the same model to apply to eating as well. When studies often confirmed this understanding, the matter became clear.

I no longer even remember if those 80/20 figures just felt right or if they came from quintile arrangements of epidemiological studies (fifths of the sample), which often show that there isn’t much benefit from optimizing eating if things are already quite good.

It is Enough when Things are “Good Enough”

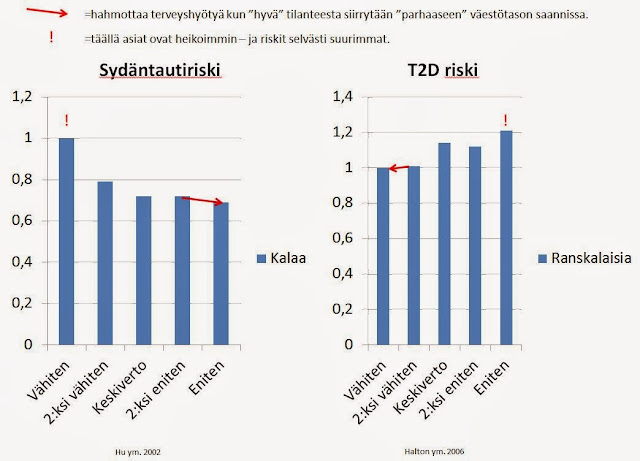

It is enough when things are quite good. To illustrate this quintile thinking from studies, I randomly selected the first quintile arrangements that came up for a few individual food/nutrient factors for this blog post, and they quite neatly illustrate the 80/20 principle.

The connection between fish consumption and heart disease risk (left) and the connection between French fry consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes (right). The benefits are minimal when moving from the second-best quintile to the best.

A brief explanation for the red arrows in the images: increasing fish consumption from once a week to five times brings only a marginal benefit; in the group that ate the second-least French fries, there was hardly any difference in the risk of type 2 diabetes compared to those who ate even less.

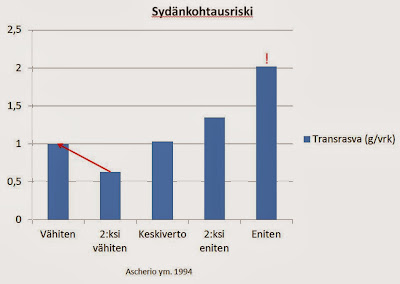

In the trans fat image, the risk actually increases when moving from the second-lowest intake to a lower one, but no major conclusions should be drawn from this, as population studies do not reveal true cause-and-effect relationships.

The core issue, however, is that fine-tuning in population studies does not seem very useful when looking at individual nutritional factors – and correspondingly, major risks are only seen when eating is completely wrong (! in the images). Avoiding poor eating is more important than optimizing a good diet.

The Overall Picture Easily Supports Weight Management

Well, I’m not claiming that fine-tuning eating in important matters wouldn’t still bring health benefits. Eating is not about individual food items but about the overall diet, and when we look at various indices that illustrate the overall diet, we most often see that the quintile eating best is clearly healthier than those eating second best.

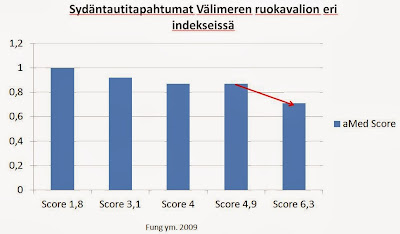

For example, this study on the Mediterranean diet index, which shows that things are clearly better in the best quintile than in the second-best quintile:

However, even in the best quintiles, it’s not about 100% good eating, but only quite good – as with the 80/20 mindset that I advocate, one would reach the best quintiles.

So it’s actually quite open what benefit optimization has for health – I guess a small benefit, but the question is whether it’s worth pursuing.

In my opinion, no, and my own guideline has long been “get the big things right carefully, and you don’t need to be so precise about the small things”. Vegetables, oils, fish, and all sorts of other sensible things should be abundant in the diet – but once those are in order, it probably doesn’t matter whether you have pizza once a month or once a year.

The same mindset naturally applies to many other things. This may not achieve the absolute perfect healthy diet, but well-being is much more than just the best possible health.

Life is not just about Focusing on Weight Management

In eating, it is generally important to consider what is being sought from it. In my work, I seek well-being, and that means many things: taste, experientiality, social flexibility, health, endurance, etc. And I communicate about eating accordingly.

Someone else may have a different value system and then acts accordingly. If the rule were even stricter than 80/20, it would mean that in eating, among other things, physiological effects (health, reason to lose weight) or even appearance would be overemphasized at the expense of other factors.

If there is no room in eating for spontaneity, surprises, indulgence, stress-free living, and trying all kinds of flavors, for example, then in my book, it’s not very good eating. Of course, some are genuinely comfortable with a rather ascetic diet, and that’s fine.

Some, on the other hand, feel comfortable with ascetic eating, but in reality, it fulfills some external goal or internal void – which is not so good in my opinion if the joy of life suffers.

For the majority, however, a very strict eating goal undermines the overall well-being effect of eating, so much so that it is noticed if one stops to think even a little.

Everyone Has a Breaking Point when They Have to “Compromise” on Their Diet.

Most people have a point in their eating after which an increasingly strict grip on healthiness starts to backfire – as hunger, cravings, and binge eating. That is, a breaking point.

And after exceeding this point, eating control and goals slip away. Someone might manage 95-100% sensible eating without setbacks, but for many, pursuing it leads from bad to worse. The 80/20 principle gives more leeway in this matter and helps many to keep eating under control.

Criticism of the 80/20 Diet

Occasionally, one hears criticism that the 80/20 rule is being lenient and coddling – when people are actually allowed to eat treats and unhealthy ingredients. Sometimes it is even feared that if even a little “slack” is allowed, people will intentionally or unintentionally take liberties.

And then there are those who believe they can control their eating only by avoiding unhealthy temptations. Well… I won’t start airing my feelings about these, but I state that I do not generally endorse these criticisms, although on an individual level, everyone certainly finds their own style.

However, let’s keep in mind that the current quality of Finns’ eating is not very good – and here is my own take on the subject.

Many Weight Management Diets are not Implemented in Practice

For most Finns, the implementation of 80/20 eating is already a huge leap forward for health and well-being, so this principle cannot possibly be detrimental to health and well-being.

Do you eat at least half a kilo of vegetables four out of five days a week, have a regular meal rhythm, good fat quality, a steady amount of protein, mostly whole grain products, avoiding excessive sugar, etc.? Good if you do, but for many, there’s work to be done.

P.S. Let’s remember, however, that the 80/20 principle is more of a mindset about eating well but seeing deviations as part of good eating, not as its “enemies”.

As long as that idea holds true, it’s probably a side issue whether we’re talking about a 90/10 ratio or a 75/25 principle. No one calculates those too precisely, do they?